October 16, 1939 – January 29, 1990

TEACHER ARTIST MUSICIAN

“He was completely content to make the kind of music for which he was created.” Alligators and Music By Donald Elliott, Illustrated by Clinton Arrowood

Books Illustrated by Clinton Arrowood:

Witch, Witch! Edited by Richard Shaw

Alligators and Music

Frogs and the Ballet

Lambs’ Tales from Great Operas

The Trilogy Written by Donald Elliott

Young Brer Rabbit and Other Trickster Tales from the Americas

Adapted by Jaqueline Shachter Weiss

Introduction by His Sister:

As Clinton’s much younger sister, I grew up with an exciting older brother who left home and entered into an adult world when I was still learning to walk. He was a second father in some ways, baby sitting, whisking me away to fascinating places, buying me presents and always adoring me! His music and art filled our home when he visited, often with musician friends, lots of friends, or when he came to stay during holiday times. I was enamored of this “pied piper,” who brought laughter and fun wherever he went. Not until I had reached my twenties did I begin to understand him intellectually and the depth of his character and talent. We shared a short “adulthood” together, even working as colleagues in teaching at one point.

Our time together was far too short, though; he died young. But, oh, the legacy he left me! His many illustrations are a vibrant part of my home now, and his voice resonates in my memory as he talked about the characters he created in pen and ink. The illustrations about a rat named Elliott who meets Henry David Thoreau have evolved into my first opus, The Adventures of Elliott Clinton Rat, III: My Journey on the Merrimack and Concord Rivers.

I have been inspired to create a different story from originally intended, but the essence of its plot and theme is similar. The central character is a rat, and he makes his way to Walden where he observes and eventually “meets” Henry David Thoreau. No longer a children’s book as it was originally intended, my interpretation is a young adult historical fiction, taking place in 1845, that introduces adolescents to the themes of the day; Transcendentalism, the Anti-Slavery Movement, Industry and the Changing Landscape, and Man’s Relationship with Nature, to name a few. The motif of “the journey” frames my story as Elliott leaves his home in Lowell and follows the same path of Henry and his brother John, who made the trip up and down the Concord River about five years before. That trip resulted in Henry Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, a memoir dedicated to his brother John who died in 1842.

Like Henry, I dedicate my work to a much loved brother, my “muse.” I hope to give his illustrations justice.

– Ellen Gaines

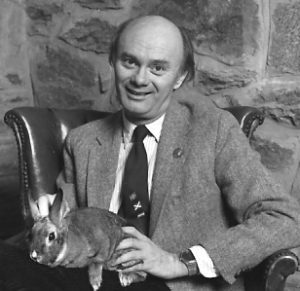

Biography of Clinton Lee Arrowood:

Born in Price, Utah, Clinton Arrowood grew up in Baltimore and attended the Maryland Institute of Art and the Peabody Conservatory of Music, where he studied under Britton Johnson, then principal flutist for the Baltimore Symphony. He attended the Vienna Academy of Music in Austria, Loyola College and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Georgia State University. He received his Master’s Degree from Dartmouth despite never having received an undergraduate degree. It seems he had accumulated so many credits at that level from various institutions that the “requirement” of an earlier degree was waved!

A true Baltimorian, Clinton Arrowood was a musician and illustrator of note for the city he embraced and which embraced him. He lived and worked there, except for occasional sabbaticals to Europe, all of his life. Best known for his pen and ink drawings of animals, Clinton created a magical world of the arts, where alligators were musicians, frogs performed in the corps de ballet, and lambs sang arias from the greatest operas ever written. Widely known for illustrating the series of books, Alligators and Music, Frogs and the Ballet, and Lambs’ Tales from Great Operas written by Donald Elliott, Arrowood’s caricatures carried a humor and poignancy that encouraged readers to reconsider their impressions of the performing arts. The late Boston Pops conductor Arthur Fiedler was one of Arrowood’s fans. When Alligators and Music was published in 1976, he said, “This book will do a great deal for two endangered species. The alligator and the musician.” The conductor of the Baltimore Symphony, Sergiu Comissiona said of the alligators Clinton created as musicians that he would “like to lead an orchestra like that.”

“Clinton’s book illustrations are remarkable for their penetrating insights into human nature,” said Lillian Randall, once research curator of manuscripts at the Walters Art Gallery and a friend. “He had a keen eye for foibles which he rendered with glee mixed with unfailing compassion.”

Arrowood also illustrated Witch, Witch, edited in 1975 by Richard Shaw, and Young B’rer Rabbit, written with Jaqueline Weiss in 1985. In addition to his books, Arrowood created posters for clients ranging from the National Aquarium to Pappagallo shoes. He even designed a series of paper dolls based on two pigs, Rodney and Emma, for a New York publishing company.

Art and music were always a part of Clinton’s persona, his very being. From his days at Peabody Clinton became known not just as an accomplished flutist, but as an artist and illustrator. His unusual programs designed for his fellow students’ recitals became much sought after and eventually collector’s items. The archives of the School are, no doubt, filled with these mementoes. The memory of his many exasperating pranks, too, remain part of Peabody lore; such as, the time he poured a box of detergent into the fountain in front of the Peabody Conservatory and the suds ran all the way down to Calvert Street!

It wasn’t just fun and games for the young Arrowood in his “chosen” art, music. Admired as a musician, he played his flute professionally in recitals with various Baltimore chamber groups and was principal flutist with the Gettysburg Symphony Orchestra for many years. He founded the Rococo Company or RococoCo for short, a quartet for baroque and rococo music.

In addition to his performing and illustrating, for 21 years he taught art history, music appreciation and flute at Garrison Forest School in Owings Mills, Maryland. He also taught for a year in the American School outside Turin, Italy. In each setting he distinguished himself as “unique, absolutely, and a madman in some ways,” according to Donald Elliott, his friend for more than 30 years. Dr. Susan Weiss of the Peabody Conservatory of Music and colleague at Garrison Forest School said, “Working with him was constant excitement; you never knew what would happen. He would throw up some art history slides and bring in everything he knew about the music and history of the period… He had a global sort of mind.” His colleague Donald Elliott with whom he collaborated on three major projects said of Clinton that, “He enjoyed life to the full; he loved it. His soul was more concerned with music and art than anyone else I’ve run into. He lived and breathed art and music.”

For his classes at Garrison, he often “dressed up.” He LOVED costumes and had a closet replete with unusual choices along-side his impeccable suits and silk shirts and interesting ties. Whether dressed in such memorable outfits as a safari costume, including a pith helmet, or in Arab robes, or even dressed as an Egyptian slave from Aida, Arrowood had a flare for the dramatic… Said Elliott of his friend’s eccentric garb, “Most people wouldn’t dare to be like that. He was nice to have around. Everyone else tended to be too damn responsible. Clinton never took anything terribly seriously – except maybe music.”

Arrowood once said, “There’s something absurd about people who take themselves too seriously.”

A fond remembrance of this philosophy occurred during a period when Clinton was performing as a fife player in a group that reenacted, in costume, of course (!), the time of the War for Independence. Elliott remembered that on one summer morning he heard flute music coming from his swimming pool. There was Clinton, standing on the diving board, dressed in Revolutionary War costume, complete with tri-corn hat and brass buttoned coat and knickers and black shoes with brass buckles, playing the flute… “Good Morning!” said Clinton, acknowledging his friend. “Anything to eat?”

Clinton NEVER took himself too seriously. The anecdotes go on… and on… and on!

But, that said, he did accomplish a serious body of work. His illustrations of animals, especially, were charming and filled with understanding. The eyes of an alligator enthralled with his music, the extended leg of a frog leaping in arabesque, or the wide-open mouth of a lamb standing with his feet (or hooves!) apart and chest filled with air to produce magnificent sound on the stage made sense somehow. Of course, it made sense that these animals could create such beauty. Weren’t they human, afterall?

With so many parallels to the naturalist and author Thoreau, flutists and philosophers and most certainly kindred spirits, it seems apt, now, that his final drawings should be about the “Man of Concord.” When Clinton died in 1990, as when Thoreau died in 1862, the town turned out to say farewell to a unique and multi-talented individual. The words of Louisa May Alcott ring true for her Mr. Thoreau as well as our Mr. Arrowood…

Thoreau’s Flute

We sighing said, “Our Pan is dead;

His pipe hangs mute beside the river

Around it wistful sunbeams quiver,

But Music’s airy voice is fled.

Spring mourns as for untimely frost;

The bluebird chants a requiem;

The willow-blossom waits for him;

The Genius of the wood is lost.”

Then from the flute, untouched by hands,

There came a low, harmonious breath:

“For such as he there is no death;

His life the eternal life commands;

Above man’s aims his nature rose.

The wisdom of a just content

Made one small spot a continent

And turned to poetry life’s prose.

“Haunting the hills, the stream, the wild,

Swallow and aster, lake and pine,

To him grew human or divine,

Fit mates for this large-hearted child.

Such homage Nature ne’er forgets,

And yearly on the coverlid

‘Neath which her darling lieth hid

Will write his name in violets.

“To him no vain regrets belong

Whose soul, that finer instrument,

Gave to the world no poor lament,

But wood-notes ever sweet and strong.

O lonely friend! he still will be

A potent presence, though unseen,

Steadfast, sagacious, and serene;

Seek not for him — he is with thee.”

Louisa May Alcott

###

Examples of Clinton Arrowood’s drawings:

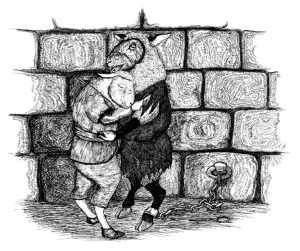

From Lambs’ Tales from Great Operas “Fidelio”

“In the illustration, we see the tender and moving reunion of Leonore and Florestan in the latter’s prison cell, as they embrace and sing a rapturous duet…”

From Frogs and the Ballet “Arabesque Penchée”

“A flaw on the part of either partner can and usually will seriously diminish the stature of an entire performance.”

From Alligators and Music “The Flute”

“If I am heard and appreciated, that’s fine, but it isn’t necessary. To be pure, one must be concerned not with what people think but with what one is. And I am pure.”

From Alligators and Music “The Harp”

“I don’t quite understand why any world must exist other than mine. There must be a reason, but I really can’t be concerned about it because my purpose in life is only to create my own special kind of radiance, and that is all I am really concerned about.”

All images © Ellen Gaines

#####

Speaking of Clinton Arrowood, “He was on intimate terms with beauty.”

By Donald Elliott, author of three of Clinton’s books and his colleague in teaching

Clinton decided some years ago, for reasons that are in themselves unimportant to adopt a new name. He settled on Klint Pfeilholz, the surname meaning, literally, Arrowood, in German. He did this with relish, immensely enjoying a private joke and thoroughly savoring the disapproval of his somewhat more staid colleagues. That name appeared in the telephone book and eventually, of course, on correspondence of all sorts. The School [Garrison Forest School], with a kind of collective sigh of resignation, changed the name on his mailbox to Arrowood slash Pfeilholz, and mail came to him thereafter under both names. Clinton liked the whole idea hugely, and after a time, deciding that Pfeilholz had run its course, he hit upon Freccia diLegno, Arrow of the Wood in Italian. Again, the name appeared in the telephone book and, once again, the name on his mailbox at school changed and now became Arrowood slash Pfeilholz slash diLegno. This, of course, thoroughly confused the poor unfortunate whose unhappy task it was to sort the mail each morning.

But who, then, was Clinton? Arrowood, Pfeilholz, diLegno – those were only names, and as Lewis Carroll knew well when he had Alice enter the woods where there were no names, there is little or no connection between things or people and their names, other than one associated simply with usefulness. Who was Clinton essentially? What was there about him that was so thoroughly unique and so inseparable from his personality? I am reminded of a short story by Henry James, an enigmatic bedeviling story called “The Figure in the Carpet.” In the story, there is a famous writer who, at one point, tells a literary magazine critic that in all his works there is a persistent and unifying thread, a single idea, a leitmotif expressed in every line, in every word. He compares it to a figure in a carpet, saying that it is like an integral part of a carpet, something that cannot be removed from it, isolated, without destroying the carpet. (No one, incidentally – including readers – ever finds out from the story just what the idea is, despite the most assiduous searching.) But that is what I am looking for with Clinton. And I think that what it has to do with is the notion that his soul was in some sense beauty itself. That is not the same as saying that he had a beautiful soul; rather, the idea is that the world of beauty – of art, of music, of nature – was an integral part of his soul. His awareness and love of beauty were not really learned things as much as they were inseparable from what he truly was, and they were, like the figure in the carpet, truly of his essence.

Clinton had a disdain for all officialdom. He could not countenance seriously most of the things that most of us take so seriously, our committees, our meetings, our schedules, our deadlines, our dread of the bill collectors, of the constabulary, of authority in general. Someone asked me a few days ago whether Clinton was an iconoclast, and I think that would not be true. An iconoclast attempts to destroy venerated institutions. Clinton didn’t want to destroy anything. He just didn’t want to have anything serious to do with those things, and he usually simply refused to be bothered by them.

But he did take art and music and beauty in general very seriously. Perhaps, however, “seriously” is not quite the right word. He loved them with all his being, all of life revolved basically around them, and anything else that intruded itself – with the possible exception of parties and dinner invitations – was merely an annoyance that he found difficult to stomach.

I don’t know whether he was what would conventionally be called a good teacher or not – he never quite got over giving tests that included items such as, “Complete the following: Johann Sebastian blank, Ludwig van blank, Wolfgang Amadeus blank” – but I do know that no student escaped the obvious love that he radiated in his classes towards all art.

And that, I think, is what he was. He drove many of us at least half crazy over the years, but all of that was overshadowed, paled into insignificance, because of what he was, and I think we all knew that he was on intimate terms with beauty, both in the concrete and the abstract. And that made him in the most important sense a great teacher and a man with a great soul.

January 1990